The national parks of the world, in addition to nature, preserve the history of wars, repressions and the struggle for independence. After the end of hostilities, the governments of many countries and the citizens themselves seek to preserve natural areas as valuable ecosystems, places of recreation and memory. Is it possible and should this practice be replicated in Ukraine?

At the Conference on the Restoration of Ukraine in Switzerland, the Minister of Environmental Protection, Ruslan Strelets, announced his intention to create 10 demonstrative national natural parks in our country. The minister’s words caused heated discussions among environmentalists: there is a high probability that such a task will lead to the introduction of a marathon in 10 national parks, which, by the way, should work perfectly even without it. On the other hand, this is an opportunity for our country, where protected areas are three times less than the average of EU countries.

In wartime, environmental protection is among the first candidates for budget cuts. Although the state, civilians and the military are players on the same team. And world experience proves that everyone benefits from the preservation of natural areas.

Nature protection in difficult times: a compromise between the state and nature

The US National Park Service (National Park Service) is a state agency that has been engaged in the management of protected areas since 1912. The most difficult period in their work came with the beginning of the Second World War. At that time, restrictions on movement were introduced in the country due to the lack of gasoline and rubber. From 1941 to 1944, in addition to a 2.5-fold decrease in the number of visitors (from 19 to 7 million/year), the national parks were threatened by the extraction of natural resources to meet military needs. It didn’t take long to reduce park employees and financial income. The problem was solved after a meeting of the Military Department, the National Park Service (NPS) and the operators of park hotels and restaurants: the military was offered recreation on the territory of national parks, and its payment from the military treasury covered the costs of technical maintenance of the parks, waste disposal and communal services. The soldiers liked the experiment so much that some of them were ready not only to enjoy fishing, but also to help with self-governance in the PZF facilities, which lacked manpower.

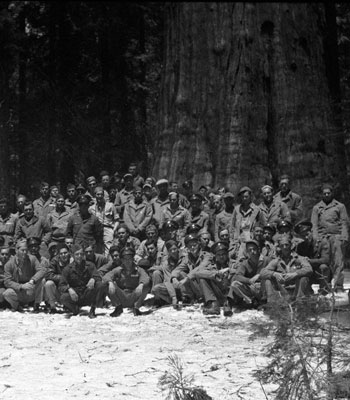

By the end of the war, the function of national parks had gone beyond formal recreation camps. Military units began to arrive at nature conservation facilities, where battles took place even during the civil war.

Soldiers pose in front of a large sequoia tree. National Park Service

Such national parks were called “patriotic”: in them, the military studied the history of the country and practiced combat maneuvers. This practice is still relevant in the USA today.[1]

In Afghanistan, which most people associate with armed conflicts rather than hypnotic natural beauty, the first national park was created in 2009 during the civil war. And although the territory of Bamyan Province does not have a unique military history, the purpose of creating the Band-e Amir National Park (Band-e Amir National Park) went far beyond nature conservation. The management of the park was to be carried out by local residents, often former refugees who had returned to their native settlements. [2] As of 2009, the civil war in Afghanistan had lasted for 30 years, which significantly undermined people’s faith in a peaceful life. The Afghan government aimed to restore national identity through the introduction of self-government in the park. It is not known whether this social mechanism worked at full capacity, but the idea was excellent. And especially appropriate for implementation in rural areas (in Afghanistan, this is 75% of the country), where people usually have close contact with both community members and the land.

However, not everything that is good for peacebuilding has the same positive effect on ecosystems. For example, the displacement of people in Virunga National Park (Virunga National Park) played a crucial role in stabilizing communities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo after the Great African War of 1998-2002. This was followed by the degradation of ecosystem services due to the overuse of forest resources for construction, fuel and food needs. [3] So the model of nature use with a social function carries many risks that must be taken into account.

Post-war recovery: nature also needs time to rest

After the war, no matter where it took place, there are enough problems that need urgent solutions. Infrastructure repair, housing construction, production expansion. As practice shows, restoration of nature is a secondary issue. However, only from 1950 to 2000, more than 80% of major armed conflicts in the world took place in “hot spots” of biodiversity – territories where local species are under threat of extinction [4]. In such a case, bequest or conservation is an effective and resource-saving solution to the problem of preserving ecosystems and their species diversity. It is wonderful if this decision is also supported by local residents, as happened in Iraq.

In the 1990s, Saddam Hussein “repressed” the Iraqi Marshes (aka Mesopotamian), along with 250,000 Marsh Arabs who had lived there for 5,000 years. Before that, soldiers of several countries of the world passed through the marshes: during the hostilities of the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s, the wetlands made it much more difficult for Iranian troops to penetrate deep into the country; served as a buffer zone in the Persian Gulf War of 1990-1991 (in fact, the war for the liberation of Kuwait, which was occupied by Iraq). It is difficult to overestimate their ecological importance: serving as a natural filter, they purify the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in their lower reaches. The waters, clean of pesticides and mineral fertilizers, head to the Persian Gulf, passing the city of Basra on the way. It started the systematic destruction of one of the largest wetland complexes in the world, with an area of up to 20,000 km².

In the early 1990s, Basra, Iraq’s second largest city, became the center of protests against Saddam Hussein’s government. Among the dissenters there were the most swamp Arabs, who, moreover, were an obstacle to the extraction of oil, which lay under the swamps. In response, the dictator ordered the bombing of their settlements. When the United Nations opposed such actions, the government prepared a plan to drain the swamps and, as a result, forcibly resettle people under the pretext of returning them to agriculture. [5]

With the fall of the Hussein regime in 2003, the Arabs returned to the marshes, which are ten times smaller than they were before the 1990s. Without waiting for a decision from above, they began to destroy the dams with their own efforts in order to return the water from the canals. Canada joined the restoration, which, as part of the Canadian-Iraqi wetlands initiative, proposed 10 scenarios for their future development. [6] In 2013, the Iraqi government announced the creation of the country’s first national park here. Post-war reconstruction of the country cannot take place separately from the rehabilitation of nature. This is a lesson for us from the inhabitants of the Mesopotamian swamps, who single-handedly reclaimed their home.

The way of life of the Marsh Arabs is very closely related to the wetlands of the Tigris and Euphrates

Photo by Agata Skowronek / Nature Iraq

The “Red Zone” in France is the general name of the protected lands where combat operations took place during the First World War. We previously mentioned this in the article “What should be the fate of Ukrainian territories damaged by explosions?”. After the war, any human activity was prohibited on 1,200 km² of territory. For some time, the French government has developed a zoning scheme based on the degree of damage. During the last 100 years, some villages that were completely destroyed were rebuilt, some remained “ghosts”. In national, regional natural parks that have been created in safe zones, such as the Montagne de Reims Regional Natural Park, the memory of fallen soldiers is commemorated with artistic residencies. [7] There are memorials in their honor in each park. Local residents collect various artifacts of the war in private museums, conduct tours along tourist trails. [8]

Trails open to visitors in ghost villages north of Verdun that were never rebuilt

Photo: Olivier Saint Hilaire

Through the years: nature as an eyewitness of events

The long-term impact of war is more often visible in the social sphere. Society is especially sensitive after the victory in the war for independence. After all, such wars cause the most painful losses. We have found examples of countries that have followed the path of creating national nature parks at the sites of key events in their national liberation wars.

Castel National Park in Israel was created after the war for its independence (or the Arab-Israeli war of 1947-1949). In the Mediterranean forests, which are under the protection of the state, you can see the trenches and bunkers of wartime. It was here that the war for Israel’s independence broke out after the Arabs rejected the UN General Assembly’s land partition plan in 1947. At that time, the Palestinian Al-Kastal served as a checkpoint on the way to Jerusalem, so it became the first settlement captured by the Jews in the War of Independence.[9] Today, the park staff conducts tours and prepares expositions in which they talk about the price of independence paid by the Israeli people.

The second most popular tourist destination in Latvia is Gauja National Park, the largest in the country, the territory of which is included in Natura 2000. Latvians, who equate the occupation of their territory by the USSR troops with the actions of the Nazis, used the opportunity to remind the younger generation about the liberation struggles , which took place on the territory of the modern park. 8 monuments were erected in the park in honor of the heroes of one Cesis battle during the liberation war with the Red Army of 1918-1920! Visitors can also learn about the events of the partisan national resistance of 1944-1957 by visiting the restored bunker of the “forest brothers” – the general name of the partisan resistance in the Baltic countries against the Soviet occupation, which began under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact – the “Border of Bralia” (“Mežabrāļi “). Thematic excursions and quests are held in museum complexes on the territory of the park. [10]

Historical uniqueness: post-war nature conservation in Ukraine

As you can see, not only biotopes, flora and fauna can be protected in nature reserves. They also “preserve” historical events. Are such examples known in Ukraine? Of course. Most often, these are restored hiding places – bunkers from the time of the UPA in dense forest thickets, which gained popularity during the war with the punitive bodies of the USSR from 1917 to the 1960s. They can be visited on ecological routes offered by national parks of Lviv region (NPP “Northern Podillia” , “Skolivski Beskydy”), Ivano-Frankivsk region (“Hutsul region”), Volyn (Kivertsivsk NPP “Tsumanska Pushcha”).

Криївка-музей в околицях села Гавареччина. Фото: офіційний сайт НПП “Північне Поділля”

http://park-podillya.com.ua/ekolohichno-piznavalnyj-turystychnyj-marshrut-markiyanovi-mistsya/

Near some of them there are only information stands, but in the NPP “Tsumanska Pushcha” in the estate, on the territory of which there was a rebel hideout, the festival of the rebel song “Pertsia’s Hideout” was held for many years. A significant number of national parks preserve historical monuments from the Second World War, such as the stronghold of the defense system of the Hungarian troops “Arpada Line” in the “Uzhanskyi” NPP or the Kyiv Fortified District (a system of fortifications, ramparts and trenches) in the “Holosiivskii” NPP.

We also find cases of gradual loss of historical memory. Kayaking in the “Buzky Gard” NPP (Mykolaiv Oblast, South Bug River), you can sail past the island and not know that it was here that the administrative center of the last palanquin of the Zaporizhzhya Army of the Novaya Sich period was located. Kinburnska spit (NPP “Biloberezhja Svyatoslava”) is known among tourists for its beaches, although it has an equally rich history. It was here that the development of the Black Sea Cossacks gained momentum under the leadership of the kosh chieftain Sydor White. There are many similar examples. Time to decide: what model of nature protection will Ukraine choose after the war?

Landowners will want to sow grain for sale as soon as possible for short-term economic gain. But isn’t it better, at least for a certain period, to conserve the lands, the level of heavy metal pollution of which is off the charts?

It is easier to forget about the period of occupation and fierce battles that took place on the territory of national parks and nature reserves, to return them to their normal mode of operation. But we also have an alternative – to give the next generations a chance to get acquainted not only with their nature, but also with their history. Set up educational stands at the places of significant battles, restore battles, conduct tours and organize festivals. In fact, all these are successful examples of unobtrusive patriotic upbringing, commemoration of the heroes of Ukraine and an important reminder of the price our people paid for freedom.

It is possible to create new nature conservation areas to achieve the bequest indicators necessary for European integration. And you can create new national parks for people. They will include special recreation programs for war veterans; places for holding events on historical, environmental topics for everyone. This is an opportunity for Ukrainians to rediscover ecosystem services related to the formation of cultural identity of ethnic and social groups, and not just consumer needs.

The nature protection potential of Ukraine is powerful and promising. At a time when the world is ready to support our state more than ever, our task is to do everything to use this support with maximum benefit – for people, the state and nature.

Valeriia Kolodezhna