The war in Ukraine has seen attacks on or disruption to wastewater treatment infrastructure in Rubizhne, Chernihiv, Skadovsk, Sloviansk, Mariupol, Siverodonetsk, Lysychansk, Popasna, Mykolaiv, Vasylivka, and likely elsewhere. Eleven separate attacks on water facilities were reported on one day alone, April 19th. These included damage to, and/or the de-energisation of filter stations, pumping stations, and sewage treatment plants across the Donetsk and Kharkiv regions1. Such an intensity of attacks on water infrastructure suggests that its targeting may be part of a deliberate strategy.

The World Health Organization has warned that damaged infrastructure can mean the spread of infectious diseases, both due to the lack of clean water and damage to sewage pipelines. The bombing of cities and towns likely resulted in dozens of broken pipelines and inoperable pumping stations, leaving hundreds of thousands of people without access to safe water. This is, of course, bad news for civilians in these locations, who are deprived of these essential environmental services. But, is there also the potential for damage to ecosystems?

Most wastewater facilities have pipelines that release treated water into freshwater or marine environments. In peacetime this is regulated and monitored. However, when the facility is damaged and not properly functional, these pipelines can be used to discharge raw sewage and/or treatment chemicals. This can be harmful to ecosystems, both through the direct effects of toxic substances, such as heavy metals, phosphorus or nitrogen, but also more indirectly through changes to temperature and concentration of dissolved oxygen and suspended solids leading to eutrophication. Discharge of sewage has so far been reported to be happening in the city of Vasylivka, with raw sewage entering the Dnipro River.

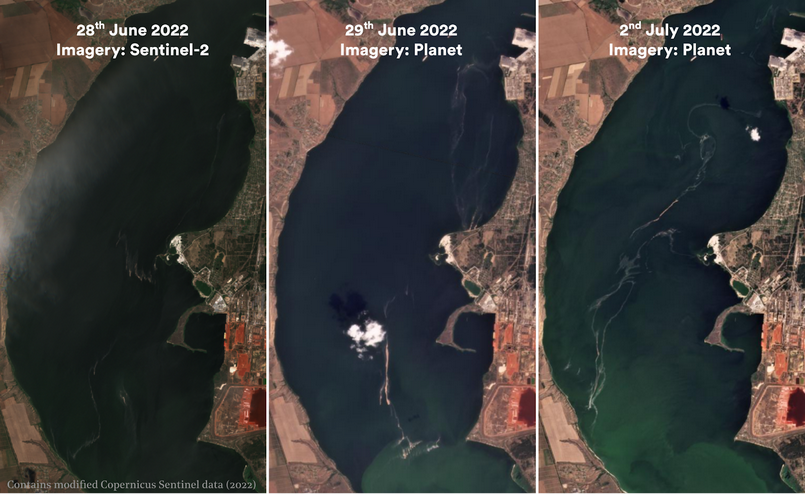

Here, we show what appears to be an unreported discharge into the Bug estuary, south of Mykolaiv, between 28 June and 15 July. The pipeline from which the discharge emanates is connected to the Halytsynove wastewater treatment facility 3.5 km inland, which treats 83% of Mykolaiv’s sewage.

To our knowledge there have been no reports from Mykolaiv on this discharge. The discharge is first visible in satellite imagery on 28 June, and extends approximately 15 km along the Bug estuary on 29 June. It is brown in color, indicating sediment or sewage, and spreads along the Bug estuary in long filaments. The volume of the discharge reduces after 3 July and becomes less brown in color, but remains visible until 15 July. It can clearly be seen to be emanating from a pipeline exit at 46.8194°N, 31.9439°E.

The common estuary of the Southern Bug and Dnipro rivers, where the waste was directed, is an important area for nature and home to the Biloberezhzhia Sviatoslava National Natural Park. The estuary is also included in two Emerald Network areas – Dniprovsko-Buzkyi Lyman, Biloberezhzhia Sviatoslava National Nature Park – because of its important aquatic habitats. It is important for many species protected by the Bern Convention, Habitat Directive and Bird Directive, including nine species of fish, two amphibians, one reptile, 66 birds, two mammal species and the Unio crassus mollusk.

One key reason for its protected status is because the Dnipro-Bug estuary is very important for bird migration. It is here that the flow of migratory birds is divided into those that migrate along the Dnipro and those that migrate along the Southern Bug River. It is also here, near the town of Ochakiv and on the Kinburn Spit, that there are stations that monitor bird migrations every year. The area around the Kinburn Spit is classified as an Important Bird Area. Thus, pollution of the Dnipro-Bug estuary may threaten many rare species and also threatens Ukraine’s ability to comply with multilateral conservation agreements.

While small discharges are common from this pipeline, this seems to be the most significant discharge in at least the past five years2. It is therefore likely to be connected to the conflict. The facilities were attacked on 7 March, but, despite damage to electrical systems and reserve equipment, it was reported that the plant could continue to operate. We could find no further reports of damage, although there was a grass fire adjacent to the wastewater treatment plant on 4 June3, which is indicative of shelling. The nearby Nika-Tera and Olvia port storage facilities have suffered large fires because of the war, and these burns and the firefighting of them may have released hazardous into the estuarine environment.

There are ongoing water supply problems in Mykolaiv. The 70-km pipeline that supplies Dnipro River water to the city and the wastewater plant is understood to be damaged in several places, and most of it lies within occupied areas. The water network was instead filled with water pumped from the Southern Bug and groundwater wells on 16 May – i.e., before the discharge at the end of June. Note, this water is more saline and requires more advanced treatment.

Mykolaiv now plans to build new water treatment facilities for supplying drinking water and to install at least 100 separate small water purification systems in the city by winter. According to Borys Dudenko, director of Mykolaivvodokanal MCP, French specialists are working to select the location of a new water intake site for Mykolaiv, focusing on the South Bug River. Any new wastewater treatment plants ought to be built in a sustainable way to meet Ukraine’s ‘green recovery’ goals, one of the seven ‘Lugano Principles’.

- According to the State Environmental Inspection of Ukraine (Letter No. 10-556/22 dated 19.05.2022)

- Based on a manual review of all Sentinel-2 scenes since the instrument was launched into orbit in late 2016 where the cloud-cover was no greater 50%. The most similar event was on 23 August 2019, but covered a much smaller area and appeared more dilute.

- A fire hotspot was detected on the NASA FIRMS platform